Revolutionary Tennis |

||

Tennis Instruction That Makes Sense |

||

All About Body Rotation

Step 4 Your Power Step 6 Stroke Commonalities Step 8 The Forehand This is a progression on body rotation compiled from Steps 4, 6, and 8 that helps clarify the unique proposition that body rotation is counter productive to success for a tennis player. It shows that while a very limited amount of upper body rotation can exist to help begin the process to racket acceleration, body rotation in and of itself is by no means solely responsible for acceleration or power. And it shows how and why to rotate your body the right way if you need to do so. As always, it turns out that less is more. From Step 4. Shifting your body weight is your body's source of power, shifting body weight empowers your limbs for the job at hand. Step 4 argues that linear momentum for shifting body weight is a simpler and more consistent method than angular momentum, and ends with the concept for advanced players that very limited upper body forward rotation to start the swing is possible. Body rotation is designed to shift weight if you're not moving into the object to begin with, or if you're standing still prior to contact. But a tennis player gets to move, and should take advantage of this huge benefit by moving into the ball instead of to the side fence.

Or look at it this way. Stand and face your computer monitor. Draw an imaginary line perpendicular to it from your body center. This line has a fixed length to it. Rotate your body to one side and notice how your imaginary line arcs inward from the monitor. As a tennis player you face the reality of a ball angling away from you. If you rotate your body during the swing, this means you're moving away from the ball at the same time it's moving away from you. Linear momentum is an easier and more reliable source of power than angular momentum. Its mathematical equation is simpler as well. When a tennis player rotates, it's overkill, counterproductive, and everything gets more complicated. What happens when a golfer or batter tries to hit the ball harder? They rotate more, and their accuracy suffers. LINEAR BODY WEIGHT SHIFT

Let me show the direction in which your weight shift should proceed. 4E shows the difference between shifting your weight forward into the ball, or shifting it "forward" toward the opponent in the direction of your stroke, which isn't forward into the ball. You shift into the ball, and there is only one direction for that.

Or, you'll rotate your body to generate momentum from an open stance because you've stopped moving, you won't step into the ball. Ironically, this momentum from rotation will not go into the ball but away from it, the largest single source of unforced forehand errors in the pros. On a replay after the pro has netted an easy forehand, notice how severely he or she rotated the body inward from the contact spot toward the opponent's side of the court, that is away from the ball. I know the idea of no body rotation is different. It runs counter to the established method. Well, if you move into the ball correctly with both feet, step into it with the front foot, shift your weight linearly into the ball, and don't rotate the body during the swing, you'll be amazed at how strong your contact is with linear momentum as a power source. Large muscle groups are still responsible for transferring weight, only now their contribution is linear, not rotational. This is a new idea. Revolutionary. LESS IS MORE SIMPLE IS BEST Let's talk about turning the body, because I know the popular idea is to "turn" the body when you take the racket back. First, when you move you automatically turn the hips and shoulders, it doesn't work the other way around, shown in diagram 4F. Movement = turning, as illustrated when hitting on-the-run forward into the court. Very few students move across the court with their shoulders parallel to the net.

Third, and last, what about the popular idea of turning the upper body a lot first, winding it up, to accelerate the stroke more via rotation? Step 6 elaborates on why this doesn't work, but for here let me refer you to diagram 4G. As long as your feet and hips (your body center) lead you into the ball there will be a limit on upper body rotation, or wind up. If, however, you allow your hips (body center) to turn more because the upper body winds up, you'll find yourself and your momentum no longer moving into the ball but away from it. Your stroke then needs more time to curve its way around to line up into the ball, and, more importantly, hitting on time becomes more difficult to achieve (more on this in Step 7).

FOR ADVANCED PLAYERS...and those who aspire to be I have received a lot of feedback regarding upper body rotation on a forehand. For advanced players the answer is yes, there is some, if you want to call it rotation. But when I asked a student of mine who's an attorney whether or not she considered what follows to be rotation, she answered, "Not really, because I'm trying to lock my torso after a point." Let me explain. What follows also applies to two handed backhands. Diagram 4H begins, like 4G before, showing the limit to the upper body's coiling, or turning, while moving forward into the ball. Next, during the forward swing, the torso re-turns to match the angle of the hips beneath it, something it wants to do quite naturally. And if the torso stops when it matches that angle it acts as a boost to get the racket going. By stopping its limited rotary movement, the torso helps accelerate the racket ON ITS OWN. This is similar to cracking a whip, where the handle stops and the rest of the whip accelerates and continues beyond it, or similar to a hammer throw, where the body prior to release stops its rotary movement to help the arms accelerate the throw.

The stroke does not accelerate as much as explained above if the shoulders continue to rotate (and the hips) in the direction of the swing and wind up facing the net. There is a point in tennis where rotary movement becomes counterproductive to stroke speed and contact control, a point easily breached when either hips or shoulders rotate to face the net in an effort to accelerate the swing. Tennis is not golf or baseball. We need to move, adjust our stride and closeness to the ball, adjust the stroke, exercise more control over the hit, keep it in a small playing area, and get ready to do it again a few more times for one point.

How can you learn the movement described in 4H? First, move into the ball and don't coil the upper body as you begin taking the racket back. Your torso will be turned slightly like your lower body. Then step into the ball with the front foot, shift your weight linearly, and swing without moving your torso or hips. A common teaching tool is to freeze after contact, that is follow through and freeze. The "freeze" stops body rotation and produces a strong hit. As a teacher I find students naturally turn the torso slightly on the forehand (good) when taking the racket back, but they naturally overrotate the shoulders forward (bad) with the swing. I guess you can't have everything. So my job is to get them to stop that forward overrotation to improve their stroke. Some players hit successfully after both moving parallel to the baseline and rotating the body. This is good enough, from time to time, but it's harder to make this style consistent because rotation compensates for not lining up properly INTO the ball to begin with. When faced with a harder or wider ball, the weakness in this style is exposed. Furthermore, this kind of player would like to have more power yet keep the ball in. How to? Cut down on the rotation, and try moving into the ball to begin with. Contact, for any sport, is preceded by shifting body weight into the contact area, you shift and hit. For tennis players it has been said that the timing of the rotation of the body (body weight shift) with the swinging of a racket onto the ball is crucial for success. Wrong sport. Tennis players need not rotate like golfers or baseball batters. Nor should they. And if your power isn't what you want even though you're moving into the ball and using linear momentum for your weight transfer, Step 5 will assist you. Using a metaphor, the perfect swing works as smoothly as a child's swing swinging back and forth between the legs of a swing set. But if Mr. Bully picked up the legs of the swing set and twisted them, the swing would no longer move smoothly, it would fly off to the side. This is what happens when you rotate the body while swinging the racket, the racket can't line up into the ball smoothly. From Step 6. Furthers the unique no-rotation proposition in order to accelerate the swing, which is itself an arc to the ball's tangent line, and begins the idea of the arm's leverage mechanics to advance acceleration. WHAT ABOUT BODY ROTATION DURING THE SWING? The swing has the potential of ruining the body's foundation and support, Step 5 . Its angular momentum and acceleration can pull the body away from the ball prior to and during contact because it heads in a direction separate from the body's focus (into the ball/ contact).

There are times when you send the ball outward from the contact spot. Here the shot is weaker and the risk of losing control is greater: hitting inside-out, changing the ball's direction (though Step 7 explains when changing the ball's direction plays to the stroke's strength), or responding to a sharply crosscourt ball (unless you hit it even more sharply crosscourt). Generally speaking, hit your best shot, through the middle of the ball. If you choose not to, understand the risk involved and don't go all out. If the body rotates after the contact it's okay. This happens, the body doesn't remain still like a statue, the stroke pulls at you. However, if the body rotates during the swing, during contact as part of the swing for power, both power and control are sacrificed. You need to separate the empowerment structure from the delivery structure. RACKET ACCELERATION Step 5 said: "To help the swing accelerate and enjoy the most strength and support from the body, the body doesn't move. Except for the swinging arm, of course. Your front shoulder remains still up through contact, 5J, acting as a brake against the force of the stroke to accelerate it. Rotation, besides moving you away from the ball and being a complicated power source unnecessary for tennis, creates friction during the swing and slows it down." Now we'll add up what we've learned here in Step 6. A stroke's acceleration lies in a direction inward from the contact spot, 6D, and is greatest when there is a common origin, our shoulder and then elbow, in our case. [Extend your arm straight away from your body, keep your shoulder still, and swing the arm side to side. Next, move your shoulder side to side and swing the arm. Compare the two speeds. When the common point, the shoulder, is still, the arm accelerates more. Furthermore, the arm pivots around this common point.] When you swing the racket and move the shoulder(s) around you lose acceleration because the common point moves. The same happens when you shift your weight along the flight line of the ball, or when you rotate, the common point moves. I've said it before, and I'll say it again: Rotation for tennis players is counterproductive to success. DON'T BE A STROKE GUZZLER Don't be a stroke guzzler. The idea is not to waste a natural resource, the arm, like an inefficient automobile engine wastes gasoline. You become a stroke guzzler when the arm moves too much as a whole, or when the arm is engaged as one unit and doesn't flex during the swing. Let's use the same example above where you extended the arm straight away from you and moved it side to side keeping the shoulder still. Do it again and notice the speed at which your hand moves. Stop, then bring the elbow in to touch your stomach and move only the forearm side to side. The hand moves faster, doesn't it? During a tennis stroke the shoulder is the first common point but you can't swing the racket with your arm completely extended or straight and expect good results. It's too slow, plus there's no leverage with the arm this way. You don't pick up a box with your arms straight, do you? The sequence of photos in 6F shows the arm extended away from you during the swing. The elbow, then, becomes a second common point, or pivot point, during your swing. As you begin your forward swing the arm bends to pivot at the elbow, bringing the elbow in closer to the side of your body, and the biceps slows down. Here the shoulder relinquishes its role as the common point and passes the torch to the elbow, whose deceleration helps the racket accelerate more. On forehands the elbows passes the torch to the wrist, but not on backhands. The photo sequence in 6G shows the arm coming in closer to the body during the forward swing. MORE ACCELERATION All in all the arm's parts compress into the body (to reduce their moments of inertia to increase the stroke's angular momentum) in an effort to whip the racket face around the arm and the body as fast as possible to hit the ball head-on. In a not so small way, this is similar to an ice skater spinning in a circle with her arms extended who then brings them in to spin faster. Of course we don't spin around, but for the small moment of a forward swing, the arms come in closer to the body to increase our racket's forward acceleration.

WHAT ABOUT THE PROS?

The 6H photo on the right shows adherence to the arm's leverage dynamic: the elbow drops and the arm comes in closer to the body for leverage and speed, and will resemble 6F top photo right during the forward swing. Though some pros extend laterally on their forehands, it's definitely more the exception than the rule. On forehands you have to get closer to the ball than you're used to because stretching, or extending, equals leverage loss. And on backhands you have to resist straightening the arm as part of the stroke's objective because that, too, equals leverage loss. From Step 8, where pros' pictures bring home this idea. And if you have to rotate, this shows you how to do it and why. ROTATION... ROTATION... Step 4 explained the adverse impact body rotation has on a tennis swing, and that little rotary movement is necessary from the back shoulder to get the swing going or even to boost it. And if a little less than that comes from the hips, its controllable, at least. Sadly, though, the idea that if a little bit is good, a lot must be better. Not. If the shoulders and hips rotate unabated, is there more power? Maybe in the world of sports scientists, who calculate that more "power" results when you rotate the greatest number of body parts and swing in arcs far away from the body. But how far do golfers rotate, or baseball players? Is their objective to face their playing field at contact? If baseball players felt they'd get more power by facing the pitcher at contact like a tennis pro facing the net, don't you think they would? But they don't, and neither should tennis players. Step 6 showed how the acceleration of an arc (stroke) is greatest when the common point to the arc remains still. In tennis, this is achieved in one of two ways. Either the common point (the back shoulder on forehands) remains pretty still after a certain point, or the front shoulder acts as a brake against it to prevent it from moving too much (common on serves). When the common point moves around unabated, this acceleration principle is lost. Today, a lot of rotary movement is sought on the forward swing. Too much. Not only does contact accuracy and quality suffer (because the ball is angling away from the direction of the rotary movement), but racket acceleration suffers as well. At the very least players with open stances and extreme grips should strive not to throw both shoulders around during the swing, they should strive at least to control the front shoulder and hand. The following photos explain.

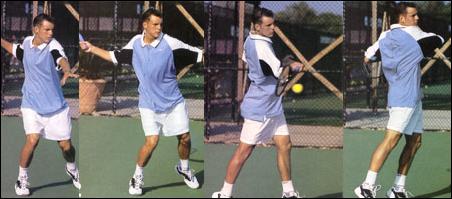

This is the entire sequence to the NBTA's killer forehand. It's clearly seen the emphasis is on "if a little is good, more must be better" idea to rotation. The rotation is exaggerated because the student's standing still prior to contact instead of moving somehow into the ball, even with the back foot. The web site's instruction for this open stance is to "keep your weight on the outside foot until after contact," which I don't see happening here. As a result of exaggerated rotation, the follow through idea becomes similarly exaggerated.

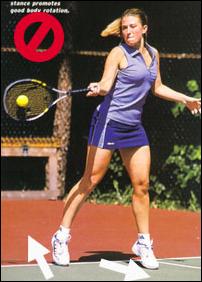

More conflict follows. The young girl in the open stance receiving serve in the ad court is meant to illustrate the value of (turning and) releasing your hips into the shot (Tennis magazine's 101 tips issue, 10/99, photo by Caryn Levy). The two arrows I added by her feet show the historical incongruity of "how to play tennis." The arrow on the left shows the ball angling away from her, that is to her right, and the arrow on the right shows the direction of her body weight shift, which is to her left, perpendicular to the net, following the sideline. The incongruity of the arrows speaks volumes. The two arrows need to intersect, the body weight shift needs to be directed at and into the ball at contact (per Step 2, 3, and 4). The photo on the right shows this happening, my feet (and thus body center) are pointed in the direction of the contact, which means I'm shifting my body weight there as well. (As a disclosure this isn't an action shot, I copied and pasted the ball onto my racket. But this form regarding the direction and placement of both feet and body equals success at contact, which is what Agassi does so darn well on the return of serve (upcoming in a later Step). HOW TO ROTATE... the right way All right, I give in. You want to rotate you say? Let me show you how to and how not to. If you're one of today's players, you're standing in an open or semi open stance prior to hitting a the ball. You're not going to step into it with the front foot, you're going to rotate your body in the direction of your shot, which is toward the net like the NBTA killer forehand above or the girl in the open stance. Or you're going to rotate so that you bring your back leg (and hip) around towards the net just as you'll bring your back shoulder around to the net. If you're going to rotate, rotate INTO THE BALL as shown in the photo above next to the girl and not toward the net. If you're going to bring your back leg around, bring it INTO THE BALL, not toward the net. If you move yourself toward the net, you're shifting your weight away from the ball because it's moving away from you.

Diagram 8E shows what it's like to bring the back leg around out of the sideways and open stance positions. It is very common today to swing that back leg or hip around in the direction of the net (the red circled arrows) instead of into the ball. You see this in all developing players, their back legs swing around to the net and their forehands suffer. If you need to rotate please rotate out into the direction of the contact spot and not inside it toward the net. Remember, rotation is by definition inward from the contact spot. Rotating inward from the contact spot defeats the purpose of empowering the shot. Rotation in and of itself does not accelerate the racket. Rotation acts more as an initial combustion agent, or first phase, to racket acceleration. I've mentioned earlier about the slight re-turning of the shoulders to initiate the forward swing for advanced players and those who want to be. The same applies to "rotating" the lower body if and when you find yourself either in a sideways position or open position. In both cases the solution is a little goes a long way. Obviously if you're sideways you can rotate more than when you're open, but then you always lose control when doing more. Power is just awesome when you rotate (though inconsistent by definition) out into the direction of the contact to encompass the ball and time the hit just right. And then it's tempting to rotate more to get more. More for more's sake doesn't exist, in so many different variations. If so, the baddest bomb in our military's arsenal would be a truly large one. The final point is you actually need to do less rotation to accelerate your racket more. It's not ironic, it's predictable. The primary responsibility to rotation is to empower the contact spot. Secondarily, rotation acts as a boosting agent for racket acceleration. If you overdo this boosting part its friction slows down the racket. Ultimately it is the arm that needs to work efficiently within itself for acceleration to be realized, and I hope I outlined that clearly enough above when describing how the arm works to swing laterally around the body. This is the reason why you see players with great forehands so "open" facing the net after the hit. It has been the acceleration of the stroke (arm) itself that has pulled the body around like this and not the other way around. It's not about the body turning (rotating) around "and pulling the racket arm along," which is often stated.

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Body rotation by definition means the body rotates inward from the contact spot, no matter the sport. From overhead, the trajectory of a tennis ball is a tangent line, angling away from the player, and it continues to angle away at contact. The direction of the body's rotation here is inward from the tangent line, inward from the contact spot (4C).

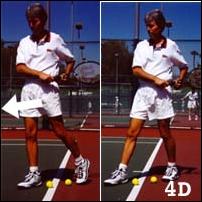

Body rotation by definition means the body rotates inward from the contact spot, no matter the sport. From overhead, the trajectory of a tennis ball is a tangent line, angling away from the player, and it continues to angle away at contact. The direction of the body's rotation here is inward from the tangent line, inward from the contact spot (4C). The length to the linear shifting of your body weight is small. This is the main advantage, there is very little "shifting" to do since you've been moving into the ball. The tennis balls placed below the center of my body in photo 4D represent this length, and the arrow shows the direction of the shift. Aggressive players will add more length to this shift by taking a longer stride.

The length to the linear shifting of your body weight is small. This is the main advantage, there is very little "shifting" to do since you've been moving into the ball. The tennis balls placed below the center of my body in photo 4D represent this length, and the arrow shows the direction of the shift. Aggressive players will add more length to this shift by taking a longer stride. If you're like most players, often your momentum has been going to the side fence. You're sideways, and to compensate you'll rotate your body to redirect your momentum more into the ball. Unavoidably, this rotation adversely impacts your stroke.

If you're like most players, often your momentum has been going to the side fence. You're sideways, and to compensate you'll rotate your body to redirect your momentum more into the ball. Unavoidably, this rotation adversely impacts your stroke. Second, if you turn first, you've turned the body and its momentum away from the ball. With this over-turn, you'll have to re-turn the body into the ball to support the stroke at contact. All of that adjustment, especially in such a short amount of time, adversely impacts any swing. Compensatory technique should not be offered as a model.

Second, if you turn first, you've turned the body and its momentum away from the ball. With this over-turn, you'll have to re-turn the body into the ball to support the stroke at contact. All of that adjustment, especially in such a short amount of time, adversely impacts any swing. Compensatory technique should not be offered as a model.

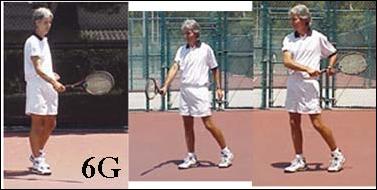

I'm including a photo here of the great Stan Smith to illustrate the movement in 4H. Stan's explaining something about hitting down the line with these two photos, but a few things prominent to

I'm including a photo here of the great Stan Smith to illustrate the movement in 4H. Stan's explaining something about hitting down the line with these two photos, but a few things prominent to  The swing's trajectory is basically an arc. Arcs accelerate from a common origin in a direction inward from their trajectory. The common origin is our shoulder to begin with, and the direction inward means inward from the contact spot, 6D, which is why 6B's head-on stroking direction feels solid and strong. This direction inward from the contact spot sends the ball back in the same direction, often more to that one side.

The swing's trajectory is basically an arc. Arcs accelerate from a common origin in a direction inward from their trajectory. The common origin is our shoulder to begin with, and the direction inward means inward from the contact spot, 6D, which is why 6B's head-on stroking direction feels solid and strong. This direction inward from the contact spot sends the ball back in the same direction, often more to that one side. 6F, left photo, shows the arm extended with the racket back. 6F top photo shows the arm coming in closer to the body during the forward swing for leverage dynamics, what you want. 6F bottom shows what to avoid, the arm extending away from your body laterally during the forward swing. 6G shows the arm folded, then unfolded during the swing for backhands in order to maintain leverage dynamics, you don't want to swing the arm straight out away from you. It's the same for two handed backhands, even though there are styles where the arms straighten and the wrists (not the elbows) act as the pivot points.

6F, left photo, shows the arm extended with the racket back. 6F top photo shows the arm coming in closer to the body during the forward swing for leverage dynamics, what you want. 6F bottom shows what to avoid, the arm extending away from your body laterally during the forward swing. 6G shows the arm folded, then unfolded during the swing for backhands in order to maintain leverage dynamics, you don't want to swing the arm straight out away from you. It's the same for two handed backhands, even though there are styles where the arms straighten and the wrists (not the elbows) act as the pivot points.

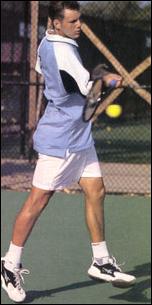

Photo 6H, left, shows the arm placement a pro often uses when taking the racket back on the forehand. The elbow is up high, the arm is drawn back in exaggerated form, the body's coiling, the stance is open. But they, too, from this position, must adhere to the arm's leverage dynamics. If they don't, and a lot of them don't, their forehands aren't what they want them to be. The exaggerated use of the arm during a pro's swing is a symptom of inefficiency, much like low gas mileage for a large automobile engine.

Photo 6H, left, shows the arm placement a pro often uses when taking the racket back on the forehand. The elbow is up high, the arm is drawn back in exaggerated form, the body's coiling, the stance is open. But they, too, from this position, must adhere to the arm's leverage dynamics. If they don't, and a lot of them don't, their forehands aren't what they want them to be. The exaggerated use of the arm during a pro's swing is a symptom of inefficiency, much like low gas mileage for a large automobile engine.

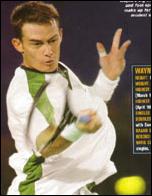

Wayne Black's forehand contact matches up with a Bollettieri Academy student (right). Wayne's front arm acts as a braking action against the back shoulder to help accelerate the swing, which is why you can see the front arm, hand, and shoulder, whereas on the NBTA student you do not. The bend of Wayne's front arm and hand mannerism both still in front or ahead of his body explain the arm's braking action, if not the arm would simply have swung uncaringly around to Wayne's left side and out of the picture, like the NBTA student. The NBTA student has rotated both shoulders around way too much, like a boxer over swinging, which has pulled his front arm and shoulder out of the picture. Yes, it could be the camera angle, but I doubt it.

Wayne Black's forehand contact matches up with a Bollettieri Academy student (right). Wayne's front arm acts as a braking action against the back shoulder to help accelerate the swing, which is why you can see the front arm, hand, and shoulder, whereas on the NBTA student you do not. The bend of Wayne's front arm and hand mannerism both still in front or ahead of his body explain the arm's braking action, if not the arm would simply have swung uncaringly around to Wayne's left side and out of the picture, like the NBTA student. The NBTA student has rotated both shoulders around way too much, like a boxer over swinging, which has pulled his front arm and shoulder out of the picture. Yes, it could be the camera angle, but I doubt it.